During my vacation for the holidays I thought that maybe I wanted some smaller project that you could fit in together with “family life” (not the easiest of endeavour!) and I got to think about some old code that I had laying about in my own little game-engine that I have thought about making public for a while. I thought it might be useful for someone else and maybe just doing some optimization work on it might be a fun little distraction!

Now about 1.5 years later, I didn’t say what holidays right, The post is finally done!

The work on this has been a constant cycle of:

- ‘Why this difference?’

- Ahh… ok!

- Take a few weeks without looking at it…

- ‘Where were I? Ahhh soon done… I just have this to check!’

- ‘WTF? why did this happen?’

- Rinse and repeat!

But here we are, finally!

memcpy_util.h

That code was a small header called memcpy_util.h containing functions to work on memory buffers, operations such as copy, swap, rotate, flip etc.

Said and done, I did set out to work on breaking it out of my own codebase, updating docs, fixing some API:s, adding a few more unittests and putting some benchmarks around the code as prep for having a go at optimizing the functions at hand.

Kudos to Scott Vokes for greatest.h and Neil Henning for the excellent little ubench.h!.

The code is published on github at the same time as this post goes live. However some quite interesting things popped out while benchmarking the code. I would say that most of this is not rocket-surgery and many of you might not find something new in here. But what the heck, the worst thing that can happen is that someone comes around and tell me that I have done some obvious errors and I’ll learn something, otherwise maybe someone else might learn a thing or two?

It should also be noted that what started as a single article might actually turn out to be a series, we’ll see what happens :)

Before we start I would like to acknowledge that I understand that writing compilers is hard and that there are a bazillion things to consider when doing so. This is only observations and not me bashing “them pesky compiler-developers”!

Prerequisites

All this work has been done on my laptop with the following specs:

CPU Intel i7-10710U

RAM 16GB LPDDR3 at 2133 MT/s (around 17GB/sec peak bandwidth)

And I’ll use the compilers that I have installed, that being

Clang: 10.0.0-4ubuntu1

GCC: g++ (Ubuntu 9.3.0-17ubuntu1~20.04) 9.3.0

And all the usual caveats on micro-benchmarking goes here as well!

Swapping memory buffers

So we’ll start where I started, by swapping memory in 2 buffers, something that is the basis of many of the other operations in memcpy_util.h, such as flipping an image. What I thought would be a quick introduction turned out to be the entire article, so lets get to swapping memory between 2 buffers!

The first thing to notice is that c do not have a memswap(). c++ do have std::swap_ranges() but we’ll get back to that later!

However, just implementing your own memswap() is a simple operation as long as you do not want to get fancy. I would consider this the simplest thing you could do!

Note: I am not handling overlap of the buffers to swap in this version as that was not something that was currently needed. Probably there should be an assert() or similar that checks for overlap however.

Generic memswap

inline void memswap( void* ptr1, void* ptr2, size_t bytes )

{

uint8_t* s1 = (uint8_t*)ptr1;

uint8_t* s2 = (uint8_t*)ptr2;

for( size_t i = 0; i < bytes; ++i )

{

uint8_t tmp = s1[i];

s1[i] = s2[i];

s2[i] = tmp;

}

}

How does such a simple function perform? It turns out “it depends” is the best answer to that question!

To answer the question we’ll add 2 benchmark functions, one to swap a really small buffer and one to swap a quite large one (4MB).

UBENCH_NOINLINE void memswap_noinline(void* ptr1, void* ptr2, size_t s)

{

memswap(ptr1, ptr2, s);

}

UBENCH_EX(swap, small)

{

uint8_t b1[16];

uint8_t b2[16];

fill_with_random_data(b1);

fill_with_random_data(b2);

UBENCH_DO_BENCHMARK()

{

memswap_noinline(b1, b2, sizeof(b1));

}

}

UBENCH_EX(swap, big)

{

const size_t BUF_SZ = 4 * 1024 * 1024;

uint8_t* b1 = alloc_random_buffer<uint8_t>(BUF_SZ);

uint8_t* b2 = alloc_random_buffer<uint8_t>(BUF_SZ);

UBENCH_DO_BENCHMARK()

{

memswap_noinline(b1, b2, BUF_SZ);

}

free(b1);

free(b2);

}

Notice how memswap() was wrapped in a function marked as noinline, this as clang would just optimize the function away otherwise.

Time to take a look at the results, we’ll look at perf at different optimization level (perf in debug/-O0 is also important!) as well as generated code-size.

All graphs in this article is generated by my own tool that I don’t recommend any one to use, but here is a link anyways! wccharts

the variance on these are quite high, so these numbers is me ‘getting feeling’ and guessing at a mean :)

Debug - -O0

Lets start with -O0 and just conclude that both clang and gcc generates basically the same code as would be expected. There is nothing magic here (and nor should there be in a debug-build!) and the code performs there after. A simple for-loop that swaps values as stated in the code.

looking at the generated assembly

Again most readers might be familiar with this but checking the generated asm on unix:es is easily done with ‘objdump’

objdump -C -d local/linux_x86_64/gcc/O2/memcpy_util_bench | lessor using the excellent little tool bat to get some nice syntax-highlighting

objdump -C -d local/linux_x86_64/gcc/O2/memcpy_util_bench | bat -l asm

clang -O0

<memswap_generic(void*, void*, unsigned long)>:

push %rbp

mov %rsp,%rbp

mov %rdi,-0x8(%rbp)

mov %rsi,-0x10(%rbp)

mov %rdx,-0x18(%rbp)

mov -0x8(%rbp),%rax

mov %rax,-0x20(%rbp)

mov -0x10(%rbp),%rax

mov %rax,-0x28(%rbp)

movq $0x0,-0x30(%rbp)

mov -0x30(%rbp),%rax

cmp -0x18(%rbp),%rax

jae 418c2b <memswap_generic(void*, void*, unsigned long)+0x7b>

mov -0x20(%rbp),%rax

mov -0x30(%rbp),%rcx

mov (%rax,%rcx,1),%dl

mov %dl,-0x31(%rbp)

mov -0x28(%rbp),%rax

mov -0x30(%rbp),%rcx

mov (%rax,%rcx,1),%dl

mov -0x20(%rbp),%rax

mov -0x30(%rbp),%rcx

mov %dl,(%rax,%rcx,1)

mov -0x31(%rbp),%dl

mov -0x28(%rbp),%rax

mov -0x30(%rbp),%rcx

mov %dl,(%rax,%rcx,1)

mov -0x30(%rbp),%rax

add $0x1,%rax

mov %rax,-0x30(%rbp)

jmpq 418bd8 <memswap_generic(void*, void*, unsigned long)+0x28>

pop %rbp

retq

nopl (%rax)

gcc -O0

<memswap_generic(void*, void*, unsigned long)>:

endbr64

push %rbp

mov %rsp,%rbp

mov %rdi,-0x28(%rbp)

mov %rsi,-0x30(%rbp)

mov %rdx,-0x38(%rbp)

mov -0x28(%rbp),%rax

mov %rax,-0x10(%rbp)

mov -0x30(%rbp),%rax

mov %rax,-0x8(%rbp)

movq $0x0,-0x18(%rbp)

mov -0x18(%rbp),%rax

cmp -0x38(%rbp),%rax

jae 62bd <memswap_generic(void*, void*, unsigned long)+0x7a>

mov -0x10(%rbp),%rdx

mov -0x18(%rbp),%rax

add %rdx,%rax

movzbl (%rax),%eax

mov %al,-0x19(%rbp)

mov -0x8(%rbp),%rdx

mov -0x18(%rbp),%rax

add %rdx,%rax

mov -0x10(%rbp),%rcx

mov -0x18(%rbp),%rdx

add %rcx,%rdx

movzbl (%rax),%eax

mov %al,(%rdx)

mov -0x8(%rbp),%rdx

mov -0x18(%rbp),%rax

add %rax,%rdx

movzbl -0x19(%rbp),%eax

mov %al,(%rdx)

addq $0x1,-0x18(%rbp)

jmp 626f <memswap_generic(void*, void*, unsigned long)+0x2c>

nop

pop %rbp

retq

Optimized - -O2/-O3

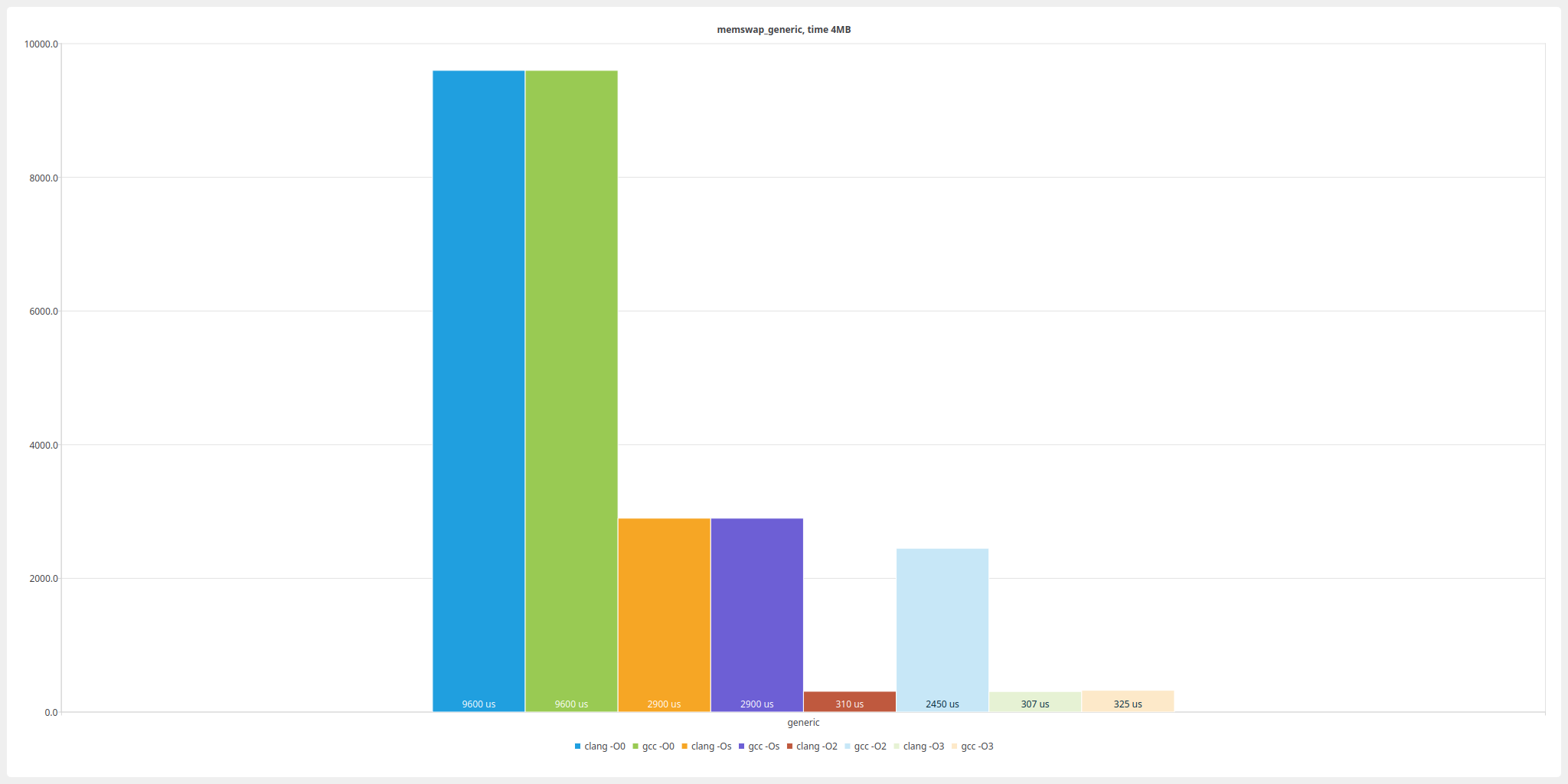

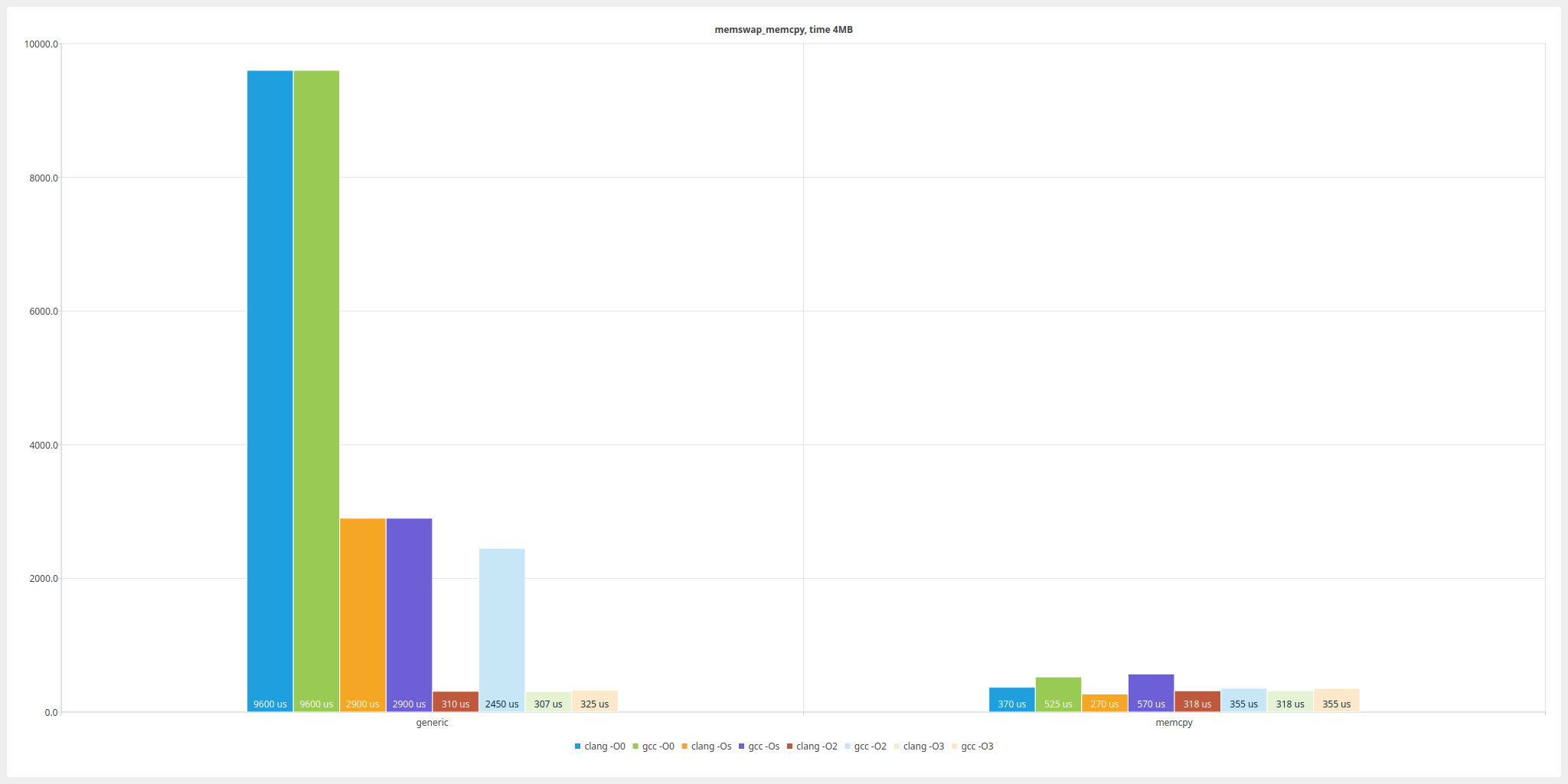

At -O2 we will see that clang finds that it can use the SSE-registers to copy the data and gives us a huge speedup at the cost of roughly 2.5x the code size. Huge in this case is 9600 us vs 310 us, i.e. near 31 times faster!

If we look at the generated assembly we can see that the meat-and-potatoes of this function just falls down to copying the data with SSE vector-registers + a preamble that handles all bytes that are not an even multiple of 16, i.e. can’t be handled by the vector registers.

Listing the assembly generated here would be quite verbose, but the main loop doing the heavy lifting looks like this:

clang -O2/-O3

# ...

# 401aa0

movups (%rdi,%rcx,1),%xmm0

movups 0x10(%rdi,%rcx,1),%xmm1

movups (%rsi,%rcx,1),%xmm2

movups 0x10(%rsi,%rcx,1),%xmm3

movups %xmm2,(%rdi,%rcx,1)

movups %xmm3,0x10(%rdi,%rcx,1)

movups %xmm0,(%rsi,%rcx,1)

movups %xmm1,0x10(%rsi,%rcx,1)

movups 0x20(%rdi,%rcx,1),%xmm0

movups 0x30(%rdi,%rcx,1),%xmm1

movups 0x20(%rsi,%rcx,1),%xmm2

movups 0x30(%rsi,%rcx,1),%xmm3

movups %xmm2,0x20(%rdi,%rcx,1)

movups %xmm3,0x30(%rdi,%rcx,1)

movups %xmm0,0x20(%rsi,%rcx,1)

movups %xmm1,0x30(%rsi,%rcx,1)

add $0x40,%rcx

add $0xfffffffffffffffe,%r9

jne 401aa0 <memswap_generic_noinline(void*, void*, unsigned long)+0xb0>

# ...

This code is fast! And if I were to guess there is some heuristic in clang that detects the pattern of swapping memory buffers and have a fast-path for it and that we are not seeing any “clever” auto-vectorization (said by “not an expert (tm)”). If I’m wrong I would love to hear about it so that I can make a clarification here!

We can also observe that clang generates identical code with -O3, this is something that will show up consistently through out this article.

Now lets look at gcc as that is way more interesting.

gcc -O2

<memswap_generic_noinline(void*, void*, unsigned long)>:

endbr64

test %rdx,%rdx

je 3ae9 <memswap_generic_noinline(void*, void*, unsigned long)+0x29>

xor %eax,%eax

nopl 0x0(%rax,%rax,1)

movzbl (%rdi,%rax,1),%ecx

movzbl (%rsi,%rax,1),%r8d

mov %r8b,(%rdi,%rax,1)

mov %cl,(%rsi,%rax,1)

add $0x1,%rax

cmp %rax,%rdx

jne 3ad0 <memswap_generic_noinline(void*, void*, unsigned long)+0x10>

retq

nopw 0x0(%rax,%rax,1)

First of we see that gcc generates really small code with -02, just 42 bytes. Code that is way slower than clang but still a great improvement over the non optimized code, 9600 us vs 2450 us, nearly 4 times faster. It has just generated a really simple loop and removed some general debug-overhead (such as keeping bytes in its own register and loading/storing it).

In -O3 however… now we reach the same perf as clang in -02, but with double the code size, what is going on here?

Well, loop-unrolling :)

using compiler explorer we can see that msvc is generating similar code as

gccfor/O2and also quite similar code for/O3, i.e. loop-unrolling!

Small - -Os

In -Os both clang and gcc generate almost identical code, and that is code very close to what gcc generates in -02. Really small, efficient “enough”… ok I guess.

Use memcpy() in chunks

So what can we do to generate better code on gcc in -O2? How about we try to just change the copy to use memcpy() instead? I.e. using memcpy() in chunks of, lets say 256 bytes? This should hopefully also improve our perf in -O0

Something like:

inline void memswap_memcpy( void* ptr1, void* ptr2, size_t bytes )

{

uint8_t* s1 = (uint8_t*)ptr1;

uint8_t* s2 = (uint8_t*)ptr2;

char tmp[256];

size_t chunks = bytes / sizeof(tmp);

for(size_t i = 0; i < chunks; ++i)

{

size_t offset = i * sizeof(tmp);

memcpy(tmp, s1 + offset, sizeof(tmp));

memcpy(s1 + offset, s2 + offset, sizeof(tmp));

memcpy(s2 + offset, tmp, sizeof(tmp));

}

memcpy(tmp, s1 + chunks * sizeof(tmp), bytes % sizeof(tmp) );

memcpy(s1 + chunks * sizeof(tmp), s2 + chunks * sizeof(tmp), bytes % sizeof(tmp) );

memcpy(s2 + chunks * sizeof(tmp), tmp, bytes % sizeof(tmp) );

}

First, lets compare with the generic implementation.

… and lets just look at the memcpy-versions by them self.

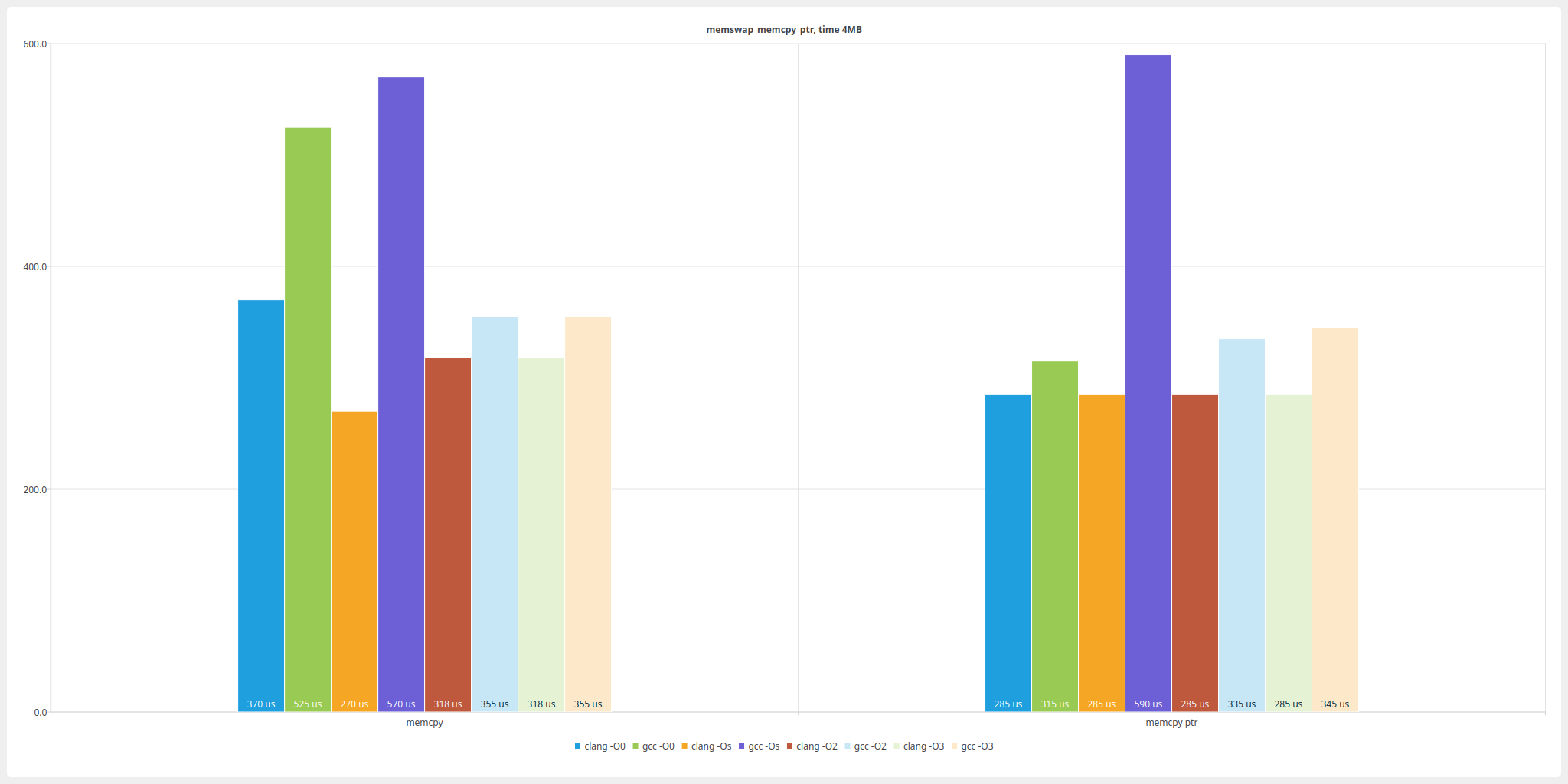

Now this is better! Both for clang ang gcc we are outperforming the ‘generic’ implementation by a huge margin in debug and we see clang being close to the same perf as -O2/-O3 in debug!:

Debug perf

| generic | GB/sec | memcpy | GB/sec | perf | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| clang | 9600 us | 0.4 | 370 us | 10.6 | 26x |

| gcc | 9600 us | 0.4 | 525 us | 7.4 | 18x |

There are a few things that we might want to dig into here!

Why is clang this much faster than gcc?

As we can see, clang is generating faster code in all configs, and usually smaller as well. The only exception when it comes to size is -Os where gcc generate really small code.

But what make the code generated by clang faster? Let’s start with a look at -O0 and the disassembly of the generated code.

The actual assembly can be found in the appendix (clang, gcc) as the listing is quite big.

I feel like I’m missing something here… is GCC inlining the copy for x bytes and if the copy is bigger it falls back to memcpy? Need to understand this better.

Looking at the disassembly we can see that gcc has decided to replace many of the calls to memcpy() (however not all of them?) with a whole bunch of unrolled ‘mov’ instructions while clang has decided to still generate calls to memcpy().

Unfortunately for gcc this inlined code is a lot slower than the system memcpy() implementation. That kind of makes sense that calling into an optimized memcpy() from debug code would yield faster execution when copying larger chunks of memory. I would guess that gcc has tried to optimized for the case where the memcpy() would be small and the jump to memcpy would eat all perf-gain? I don’t know what heuristics went into this but I’ll ascribe it to “it is hard to write a compiler and what is best for x is not necessarily best for y”.

One thing we can try is to get gcc to call memcpy() by calling it via a pointer and by that not inline it. Something like this?

inline void memswap_memcpy( void* ptr1, void* ptr2, size_t bytes )

{

void* (*memcpy_ptr)(void*, const void*, size_t s) = memcpy;

uint8_t* s1 = (uint8_t*)ptr1;

uint8_t* s2 = (uint8_t*)ptr2;

char tmp[256];

size_t chunks = bytes / sizeof(tmp);

for(size_t i = 0; i < chunks; ++i)

{

size_t offset = i * sizeof(tmp);

memcpy_ptr(tmp, s1 + offset, sizeof(tmp));

memcpy_ptr(s1 + offset, s2 + offset, sizeof(tmp));

memcpy_ptr(s2 + offset, tmp, sizeof(tmp));

}

memcpy_ptr(tmp, s1 + chunks * sizeof(tmp), bytes % sizeof(tmp) );

memcpy_ptr(s1 + chunks * sizeof(tmp), s2 + chunks * sizeof(tmp), bytes % sizeof(tmp) );

memcpy_ptr(s2 + chunks * sizeof(tmp), tmp, bytes % sizeof(tmp) );

}

First observation, clang generate the same code for all configs except -O0.

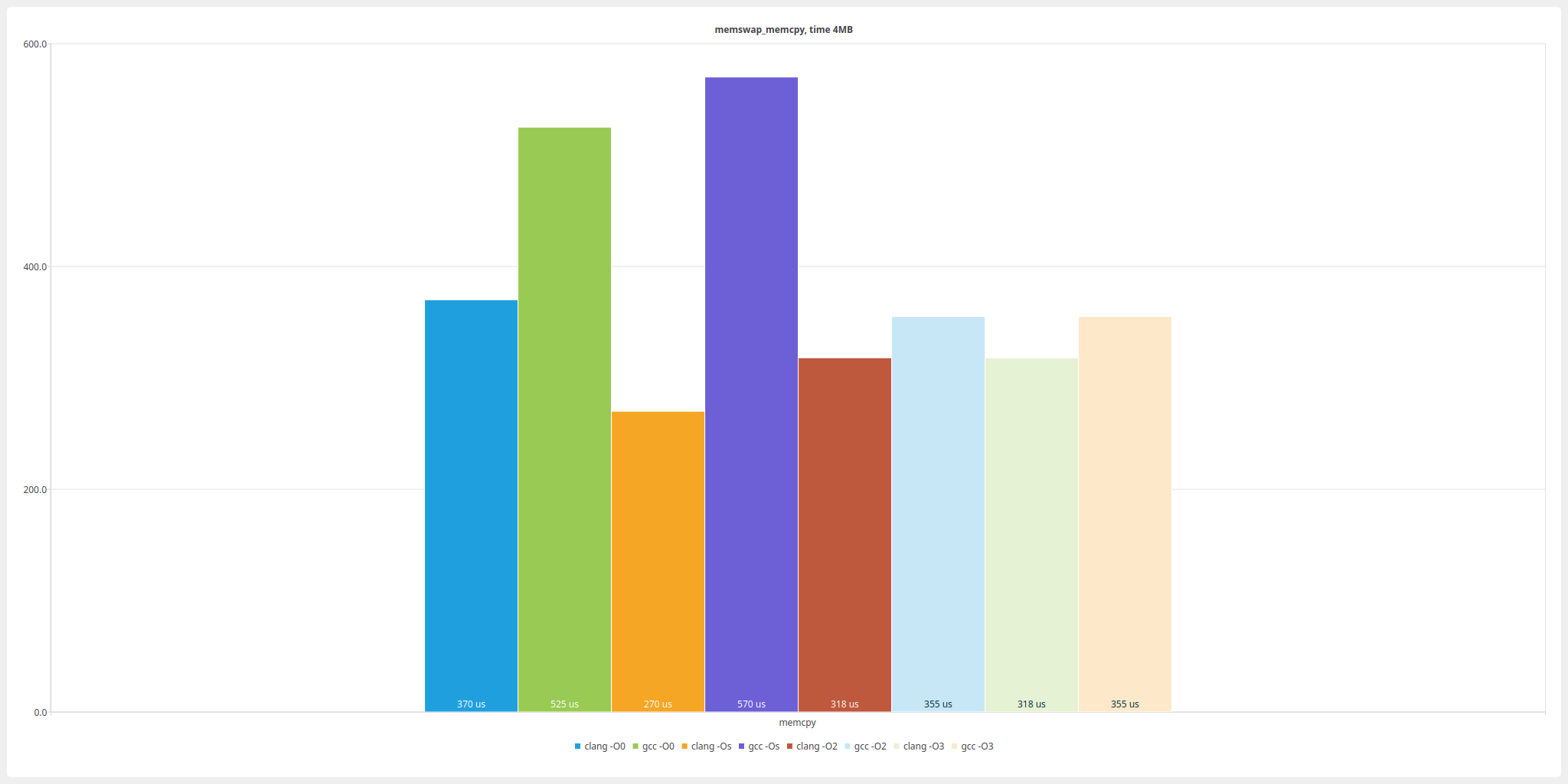

Secondly, in -O0, we see WAY better perf on gcc and slightly better on clang. Calling into an optimized memcpy(), albeit via a pointer, instead of a bunch of unrolled mov instructions seem like a smart thing to do :)

Next up, lets have a look at -O2/-O3, here we see that clang still decide to just call memcpy() and be done with it while gcc tries to be smart and add an inlined vectorized implementation using the SSE-registers (this is the same vectorization that it uses when its just a pure memcpy()).

Unfortunately for GCC it’s generated memcpy-replacement is both slower and bulkier than just calling memcpy() directly resulting in both slower and bigger code :(

An interesting observation here is that in the measurements we see that clang is faster when going through a function pointer than directly calling memcpy(). I found this quite odd and checked the generated assembly… and that is identical! As I wrote earlier, all the usual caveats on micro benchmarking apply :D

memcpy(), to inline or not to inline, thats the question?

Calling memcpy or inlining, how do the compiler decide if it should call the system memcpy() or generate its own? It is not really clear to me and it would be interesting to dig into but I feel that it is out of the scope of this already big post. Maybe there will be a follow up some day :)

Manual vectorization with SSE

Next up… we found on the generic implementations that clangs vectorization performed quite well… and what the compiler can do we can do as well right?

inline void memswap_sse2( void* ptr1, void* ptr2, size_t bytes )

{

size_t chunks = bytes / sizeof(__m128);

// swap as much as possible with the sse-registers ...

for(size_t i = 0; i < chunks; ++i)

{

float* src1 = (float*)ptr1 + i * (sizeof(__m128) / sizeof(float));

float* src2 = (float*)ptr2 + i * (sizeof(__m128) / sizeof(float));

__m128 tmp =_mm_loadu_ps(src1);

_mm_storeu_ps(src1, _mm_loadu_ps(src2));

_mm_storeu_ps(src2, tmp);

}

// ... and swap the remaining bytes with the generic swap ...

uint8_t* s1 = (uint8_t*)ptr1 + chunks * sizeof(__m128);

uint8_t* s2 = (uint8_t*)ptr2 + chunks * sizeof(__m128);

memswap_generic(s1, s2, bytes % sizeof(__m128));

}

Again lets compare with the generic implementation.

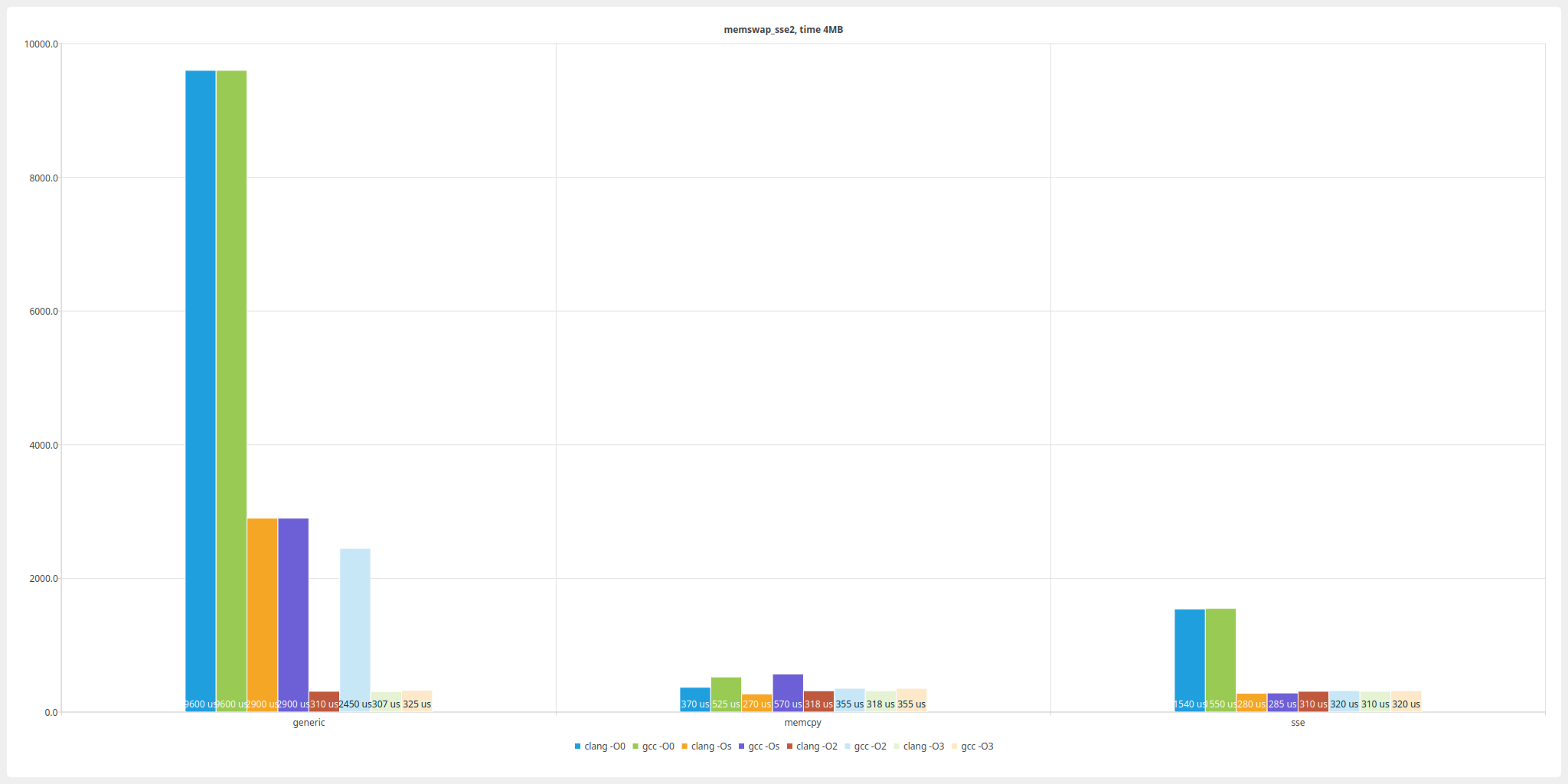

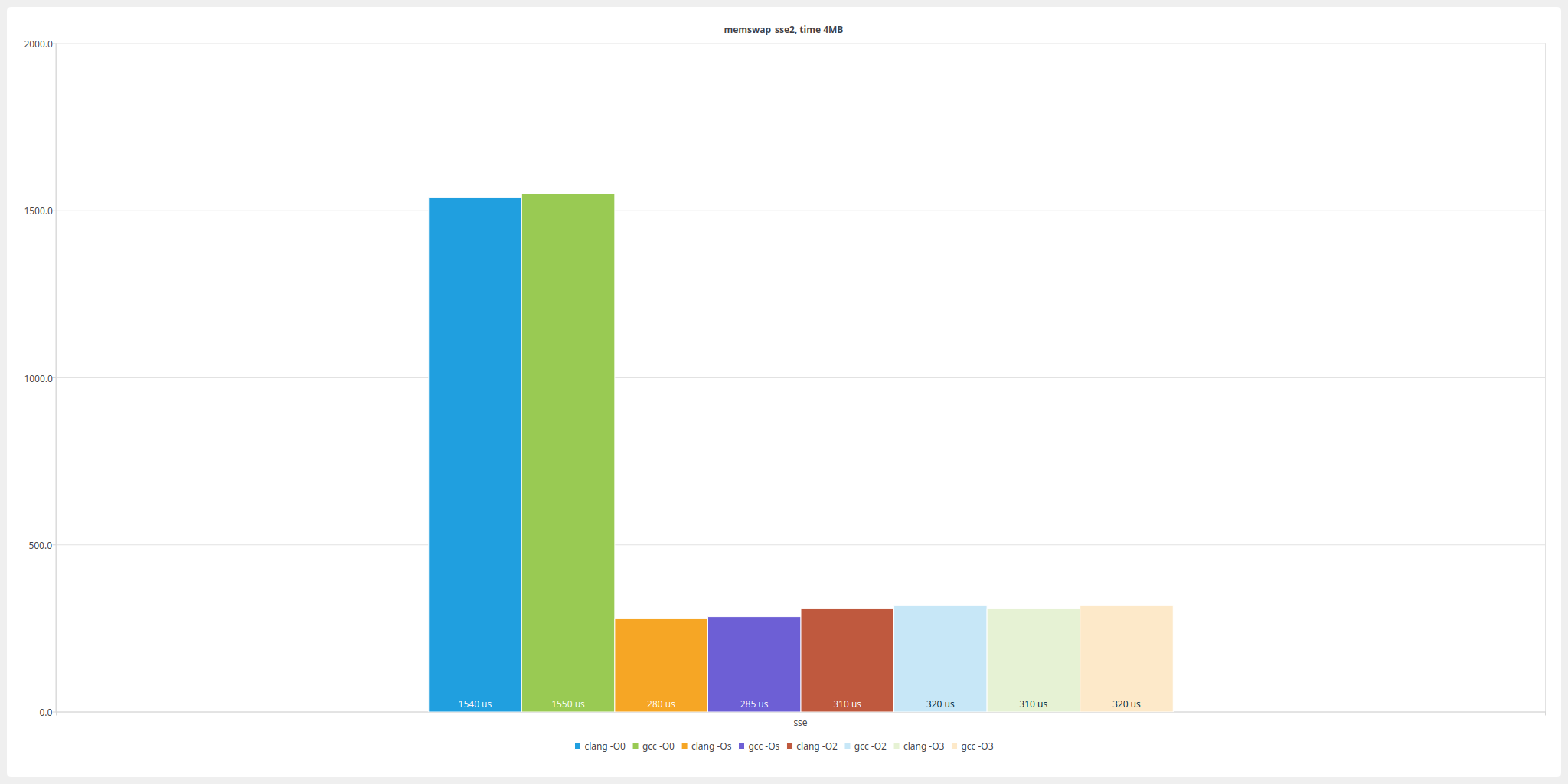

… and the sse2-versions among them selfs.

Data in table form

| generic | GB/sec | memcpy | GB/sec | sse2 | GB/sec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

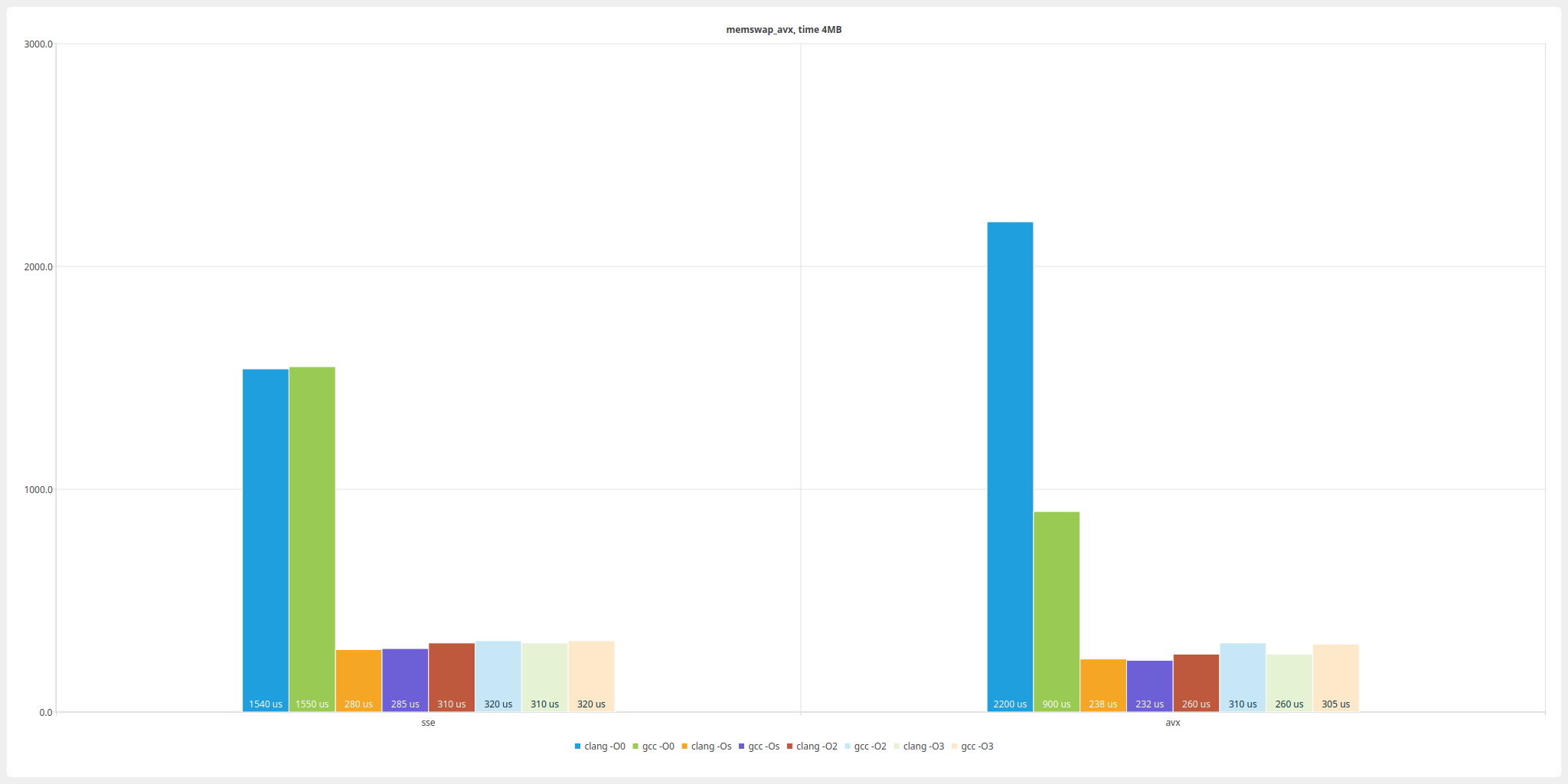

| clang -O0 | 9600 us | 0.4 | 370 us | 10.56 | 1540 us | 2.54 |

| clang -Os | 2900 us | 1.35 | 270 us | 14.47 | 280 us | 13.95 |

| clang -O2 | 310 us | 12.6 | 318 us | 12.28 | 310 us | 12.60 |

| clang -O3 | 307 us | 12.6 | 318 us | 12.28 | 310 us | 12.60 |

| gcc -O0 | 9600 us | 0.4 | 525 us | 7.44 | 1550 us | 2.54 |

| gcc -Os | 2900 us | 1.35 | 570 us | 6.85 | 285 us | 13.71 |

| gcc -O2 | 2450 us | 1.59 | 355 us | 11.0 | 320 us | 12.21 |

| gcc -O3 | 325 us | 12.0 | 355 us | 11.0 | 320 us | 12.21 |

Now we’r talking. By sacrificing support on all platforms and only focusing on x86 we can get both compilers to generate code that can compete with the calls to memcpy() in all but the -O0 builds. IMHO that is not surprising as we are comparing an optimized memcpy() against unoptimized code, however 1.5ms compared to the generic implementations 9.6ms is nothing to scoff at!

For better perf it seems it might be worth calling the memcpy-version in debug, but should one select different code-paths depending on optimization level… not really sure? Maybe hide it behind a define and let the user decide?

Or why not just make a pure assembly implementation right away?

Manual vectorization with AVX

So if going wide with SSE registers was this kind of improvement, will it perform even better if we go wider with AVX? Lets try it out!

inline void memswap_avx( void* ptr1, void* ptr2, size_t bytes )

{

size_t chunks = bytes / sizeof(__m256);

// swap as much as possible with the avx-registers ...

for(size_t i = 0; i < chunks; ++i)

{

float* src1 = (float*)ptr1 + i * (sizeof(__m256) / sizeof(float));

float* src2 = (float*)ptr2 + i * (sizeof(__m256) / sizeof(float));

__m256 tmp = _mm256_loadu_ps(src1);

_mm256_storeu_ps(src1, _mm256_loadu_ps(src2));

_mm256_storeu_ps(src2, tmp);

}

// ... and swap the remaining bytes with the generic swap ...

uint8_t* s1 = (uint8_t*)ptr1 + chunks * sizeof(__m256);

uint8_t* s2 = (uint8_t*)ptr2 + chunks * sizeof(__m256);

memswap_generic(s1, s2, bytes % sizeof(__m256));

}

They seem fairly similar in perf even as the AVX implementation is consistently slightly faster in optimized builds. Clang generally performing a bit better than gcc perf-wise.

However the most interesting thing is seeing that clang in -O0 makes such a poor job of AVX compared to SSE while gcc seems to handle it just fine, actually generating faster -O0-code than the SSE-versions.

We’ll get to that later, but first …

Unrolling!

Another thing we found when looking at clangs generated SSE-code was that it was unrolled to do 4 swaps each iteration of the loop. Will that bring us better perf in our sse and avx implementations? lets try!

size_t chunks = bytes / sizeof(__m128);

for(size_t i = 0; i < chunks / 4; ++i)

{

float* src1_0 = (float*)ptr1 + (i + 0) * (sizeof(__m128) / sizeof(float));

float* src1_1 = (float*)ptr1 + (i + 1) * (sizeof(__m128) / sizeof(float));

float* src1_2 = (float*)ptr1 + (i + 2) * (sizeof(__m128) / sizeof(float));

float* src1_3 = (float*)ptr1 + (i + 3) * (sizeof(__m128) / sizeof(float));

float* src2_0 = (float*)ptr2 + (i + 0) * (sizeof(__m128) / sizeof(float));

float* src2_1 = (float*)ptr2 + (i + 1) * (sizeof(__m128) / sizeof(float));

float* src2_2 = (float*)ptr2 + (i + 2) * (sizeof(__m128) / sizeof(float));

float* src2_3 = (float*)ptr2 + (i + 3) * (sizeof(__m128) / sizeof(float));

__m128 tmp0 = _mm_loadu_ps(src1_0);

__m128 tmp1 = _mm_loadu_ps(src1_1);

__m128 tmp2 = _mm_loadu_ps(src1_2);

__m128 tmp3 = _mm_loadu_ps(src1_3);

_mm_storeu_ps(src1_0, _mm_loadu_ps(src2_0));

_mm_storeu_ps(src1_1, _mm_loadu_ps(src2_1));

_mm_storeu_ps(src1_2, _mm_loadu_ps(src2_2));

_mm_storeu_ps(src1_3, _mm_loadu_ps(src2_3));

_mm_storeu_ps(src2_0, tmp0);

_mm_storeu_ps(src2_1, tmp1);

_mm_storeu_ps(src2_2, tmp2);

_mm_storeu_ps(src2_3, tmp3);

}

memswap_sse2((float*)ptr1 + chunks * (sizeof(__m128) / sizeof(float)),

(float*)ptr2 + chunks * (sizeof(__m128) / sizeof(float)),

bytes - chunks * sizeof(__m128));

First of, it seems that we gain a bit of perf yes, nothing major but still nothing to scoff at! However what I find mostly interesting is how, in -O0, clang generate similar code as gcc for SSE, but way worse for AVX, same as for the non-unrolled case? What’s going on here?

If we inspec the generated assembly for the sse-version, both clang and gcc has generated almost the same code. There is an instruction here and there that are a bit different, but generally the same.

However for AVX the story is different…

first of, if we look at code size, we see that clang has generate a function clocking in at 1817 byte while gcc is clocking in at 1125 bytes.

All of this diff in size is taken up by the fact tha gcc has decided to use vinsertf128 and vextractf128 while clang decide to do the same move to and from registers with your plain old mov and quite a few of them.

I guess gcc has just been coming further in their AVX support than clang. This is not my field of expertise, so I might have missed something crucial here. If I have, please point it out!

How about std::swap_ranges() and std::swap()?

Now I guess some of you ask yourself, why doesn’t he just use what is given to him by the c++ standard library? It is after all “standard” and available to all by default, it should be at least decent right?

So let’s add some benchmarks and just test it out! According to all info I can find std::swap_ranges() is the way to go.

So lets add the benchmark, run and… OH NO!

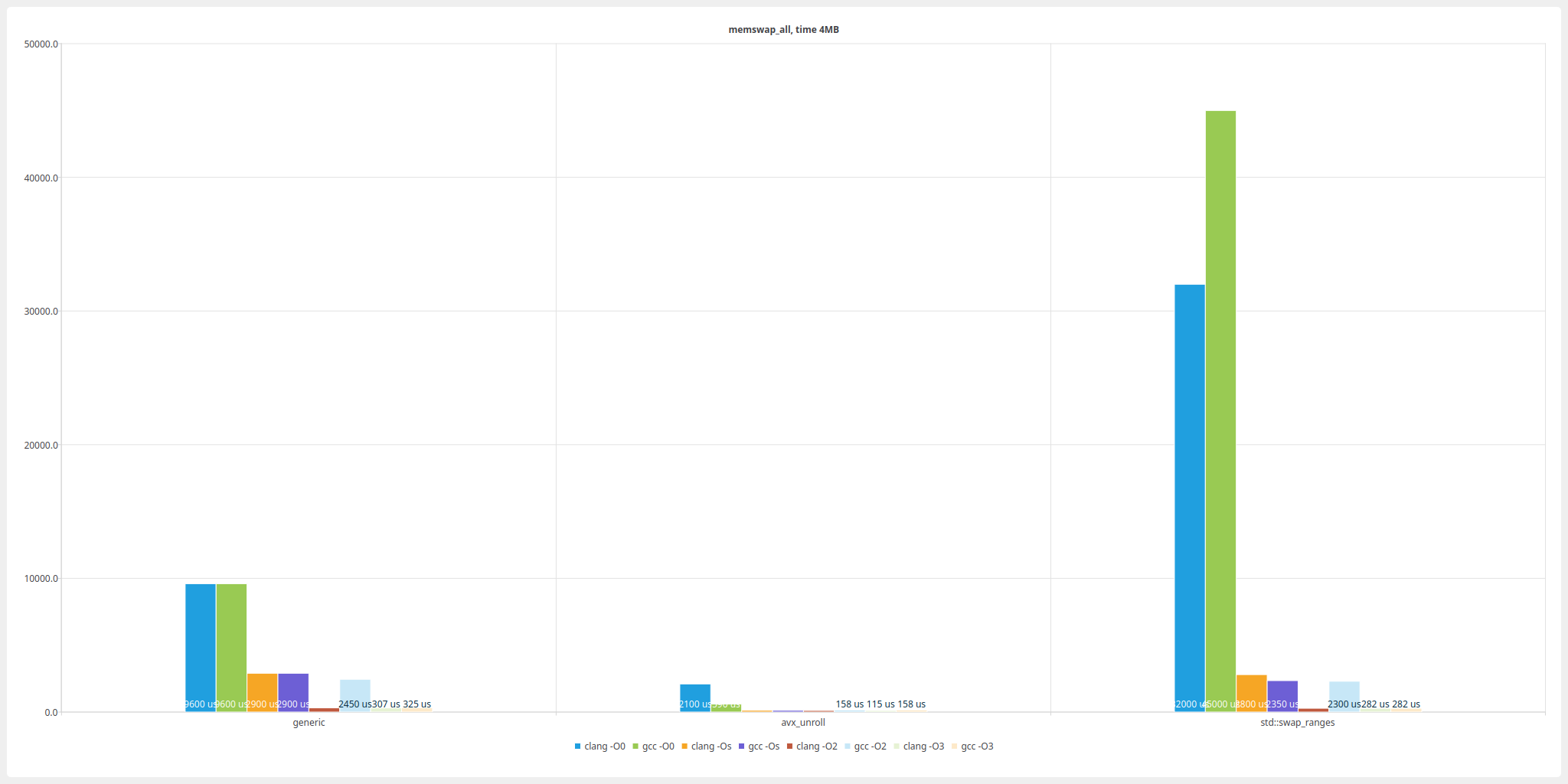

On my machine, with -O0, it runs in about 3.3x the time on clang and 4.7x slower on gcc than the generic version we started of with! And compared to the fastest ones that we have implemented ourself its almost 112x slower in debug! Even if we don’t “cheat” and call into an optimized memcpy() we can quite easily device a version that run around 32x faster!

Even the optimized builds only reach the same perf as we do with the standard ‘generic’ implementation we had to begin with, not to weird as if you look at its implementation it is basically a really complex way of writing what we had in the generic case!

I’m leaving comparing compile-time of “generic loop” vs “memcpy_util” vs “std::swap_ranges()” as an exercise for the reader!

So lets dig into why the performance is so terrible in debug for std::swap_ranges… should we maybe blame the “lazy compiler devs”? Nah, not really, the compiler is really just doing what it was told to do, and it was told to generate a lot of function-calls!

Lets take a trip to compiler explorer and have a look at what assembly is actually generated for this.

std::swap_ranges()

swap_it():

push rbp

mov rbp, rsp

mov eax, OFFSET FLAT:b1+4096

mov edx, OFFSET FLAT:b2

mov rsi, rax

mov edi, OFFSET FLAT:b1

call unsigned char* std::swap_ranges<unsigned char*, unsigned char*>(unsigned char*, unsigned char*, unsigned char*)

nop

pop rbp

ret

Only 15 lines of assembly… nothing really interesting here, we’ll have to dig deeper. Time to tell compiler explorer to show “library functions”

std::swap_ranges() - expanded

unsigned char* std::swap_ranges<unsigned char*, unsigned char*>(unsigned char*, unsigned char*, unsigned char*):

push rbp

mov rbp, rsp

sub rsp, 32

mov QWORD PTR [rbp-8], rdi

mov QWORD PTR [rbp-16], rsi

mov QWORD PTR [rbp-24], rdx

.L3:

mov rax, QWORD PTR [rbp-8]

cmp rax, QWORD PTR [rbp-16]

je .L2

mov rdx, QWORD PTR [rbp-24]

mov rax, QWORD PTR [rbp-8]

mov rsi, rdx

mov rdi, rax

call void std::iter_swap<unsigned char*, unsigned char*>(unsigned char*, unsigned char*)

add QWORD PTR [rbp-8], 1

add QWORD PTR [rbp-24], 1

jmp .L3

.L2:

mov rax, QWORD PTR [rbp-24]

leave

ret

swap_it():

push rbp

mov rbp, rsp

mov eax, OFFSET FLAT:b1+4096

mov edx, OFFSET FLAT:b2

mov rsi, rax

mov edi, OFFSET FLAT:b1

call unsigned char* std::swap_ranges<unsigned char*, unsigned char*>(unsigned char*, unsigned char*, unsigned char*)

nop

pop rbp

ret

void std::iter_swap<unsigned char*, unsigned char*>(unsigned char*, unsigned char*):

push rbp

mov rbp, rsp

sub rsp, 16

mov QWORD PTR [rbp-8], rdi

mov QWORD PTR [rbp-16], rsi

mov rdx, QWORD PTR [rbp-16]

mov rax, QWORD PTR [rbp-8]

mov rsi, rdx

mov rdi, rax

call std::enable_if<std::__and_<std::__not_<std::__is_tuple_like<unsigned char> >, std::is_move_constructible<unsigned char>, std::is_move_assignable<unsigned char> >::value, void>::type std::swap<unsigned char>(unsigned char&, unsigned char&)

nop

leave

ret

std::enable_if<std::__and_<std::__not_<std::__is_tuple_like<unsigned char> >, std::is_move_constructible<unsigned char>, std::is_move_assignable<unsigned char> >::value, void>::type std::swap<unsigned char>(unsigned char&, unsigned char&):

push rbp

mov rbp, rsp

sub rsp, 32

mov QWORD PTR [rbp-24], rdi

mov QWORD PTR [rbp-32], rsi

mov rax, QWORD PTR [rbp-24]

mov rdi, rax

call std::remove_reference<unsigned char&>::type&& std::move<unsigned char&>(unsigned char&)

movzx eax, BYTE PTR [rax]

mov BYTE PTR [rbp-1], al

mov rax, QWORD PTR [rbp-32]

mov rdi, rax

call std::remove_reference<unsigned char&>::type&& std::move<unsigned char&>(unsigned char&)

movzx edx, BYTE PTR [rax]

mov rax, QWORD PTR [rbp-24]

mov BYTE PTR [rax], dl

lea rax, [rbp-1]

mov rdi, rax

call std::remove_reference<unsigned char&>::type&& std::move<unsigned char&>(unsigned char&)

movzx edx, BYTE PTR [rax]

mov rax, QWORD PTR [rbp-32]

mov BYTE PTR [rax], dl

nop

leave

ret

std::remove_reference<unsigned char&>::type&& std::move<unsigned char&>(unsigned char&):

push rbp

mov rbp, rsp

mov QWORD PTR [rbp-8], rdi

mov rax, QWORD PTR [rbp-8]

pop rbp

ret

Ouch… we have call instructions generated for std::remove_reference, std::enable_if and std::iter_swap (so much for zero-cost abstractions)… and there is nothing wrong with that from a compiler standpoint, you told it that you had functions that needed to be called so the compiler will generate the functions call!

FYI the same code is generated for std::swap, std::array and similar constructs as well.

Why did the code end up like this? I can’t really answer that as I have neither written or, with an emphasis on, maintained a standard library implementation. I see that the generic code that we have there today lead to less code to maintain and maybe the concept of swapping buffers of memcpy:able data is not something that std::swap_ranges isn’t often used for but there is absolutely room for improvement here.

Just having a top-level check for “can be moved via memcpy()” and have a plain for-loop in that case would generate faster code in debug-builds for all of us.

But as stated, I have not worked on a standard library implementation nor have I maintained one (a “standard library” for a commercial, AAA game-engine however!) so I’m sure that I have missed lots of details here ¯\(ツ)/¯

What rubs me the wrong way with this is that there is nothing in the spec of std::swap_ranges that say that it has to be implemented(!) generically for all underlying types. If the type can be moved with a memcpy it could be implemented by a simple loop (or even better something optimized!).

This was done in Apex:s containers recently and saved us a BUNCH of perf, especially in debug-builds but also in optimized builds!

This is code and APIs used by millions of developers around the world, all of them having less of a chance to use a debug-build to track down their hairy bugs and issues. I can see the logic behind “just have one implementation for all cases” and how that might make sense if you look at code from a “purity” standpoint but in this case there are such a huge amount of developers that are affected that imho that “purity” is not important at all. Your assignment as standard library developers should not be to write readable and “nice” code (or maybe it is and in that case that is not the right focus!) it is to write something that work well for all the developers using your code! And that goes for non-optimized builds as well!

We have only tested on 4MB, how do we fare on smaller and bigger buffers?

Up until now we have only checked performance on 4MB buffers but what happen in smaller and bigger buffers? Lets add some tests over a range of buffer sizes, we’ll add benchmarks on swapping buffers from 16 bytes up to 2GB in “reasonable” intervals and plot them against each other as a byte/sec vs buffer-size. For comparison we’ll also add in a pure memcpy() perf test as a benchmark as well.

We’ll split this section in debug and release build so let the graph-fest begin!

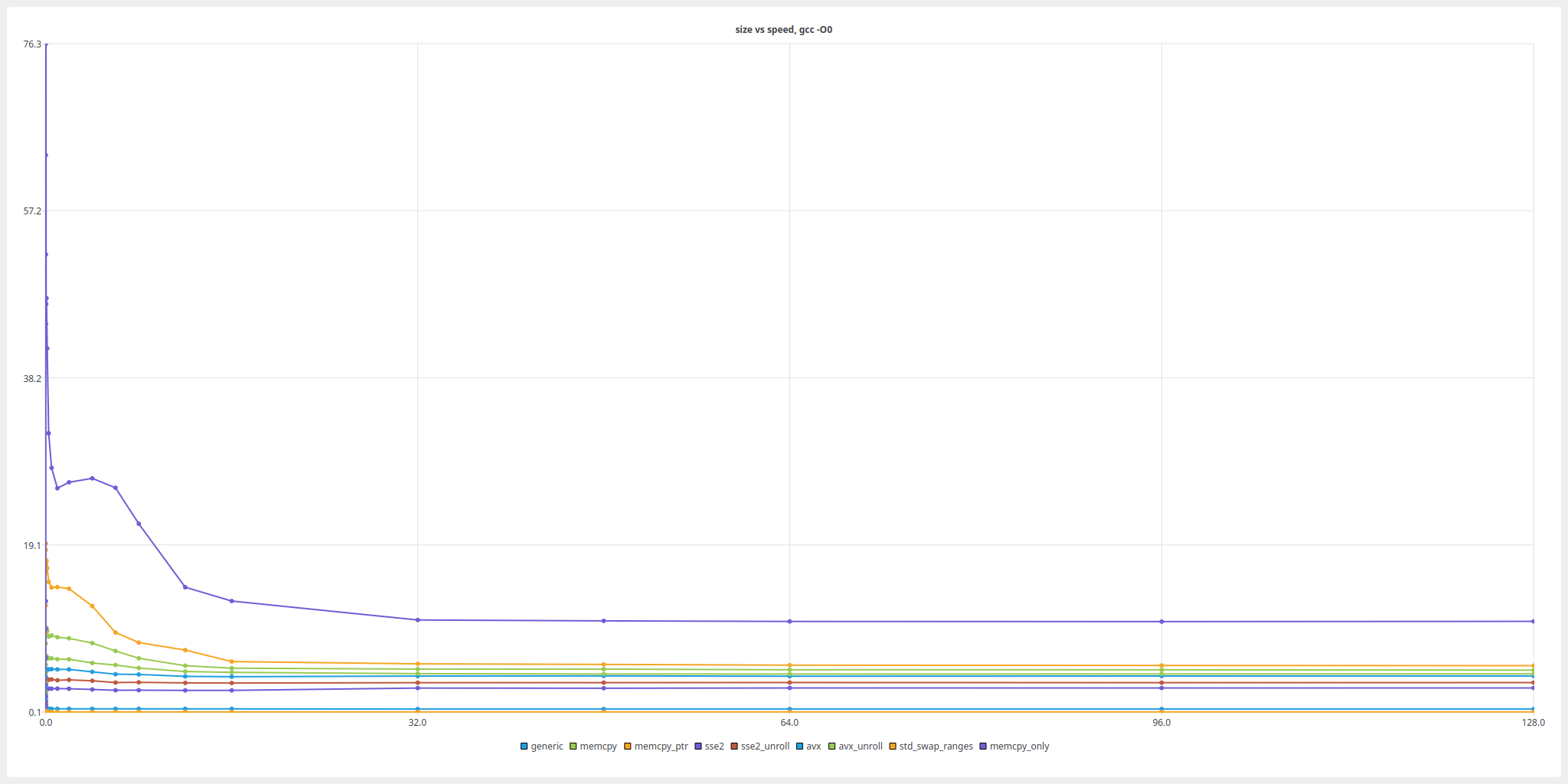

Different buffer-sizes, -O0

Fist of, some graphs for all our implementations.

It is clear that we have a point ( around 12MB ) where perf flattens out for all implementations and everything above that it not really interesting, this for both compilers. It just happens to be that my machine has an L3 cache size of 12 MB! Another observation is that after this point the best implementation of memswap is roughly half the perf of a pure memcpy which also make sense as that is the mount of memory that has to be copied in a swap :D

So conclusion 1, our best implementation in debug (just using memcpy()) saturates the memory-bus! Hard to beat that!

We also see that all other implementations seem to be CPU-bound on different levels as they basically perform the same on all buffer-sizes and is NOT reaching what the memory on the machine should support.

Cpu-cache sizes can be queried on via

cat /sys/devices/system/cpu/cpu0/cache/index[0-3]/size

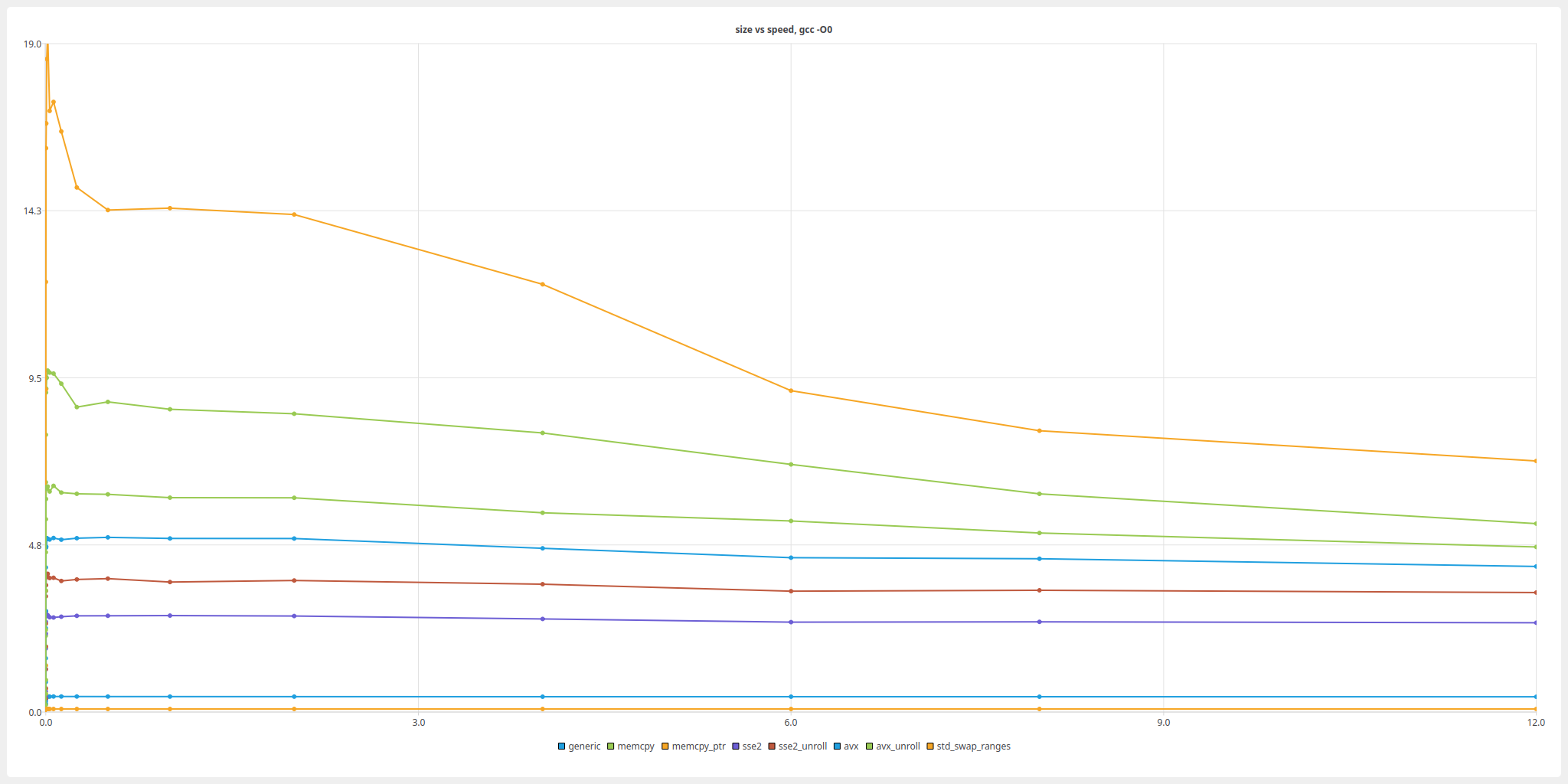

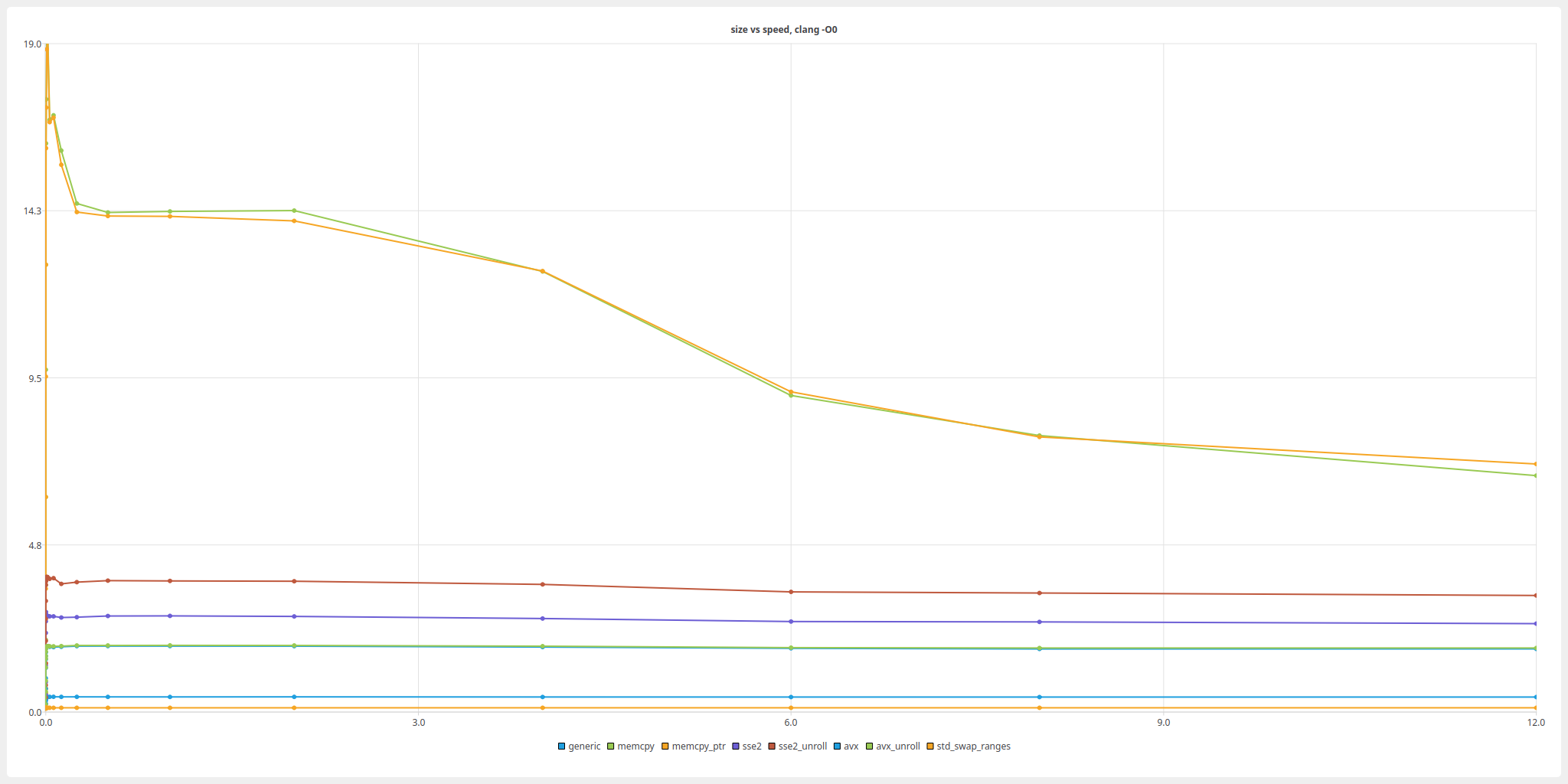

Lets remove memcpy()-only and zoom in on sizes under 12MB!

It is clear than calling into memcpy is performing well on both compilers. It is also clear here that, as we concluded earlier, that GCC:s inlining of memcpy() is not doing it any favours here as going via a pointer (i.e. tricking gcc not to inline) is so much faster!

We also see how much better gcc performs with AVX than clang, we have dug into this before but these graphs shows it clearly.

Do we have to mention the “flat-line” that is std::swap_ranges()?

Other than this, the both compilers do a similar job an all implementations!

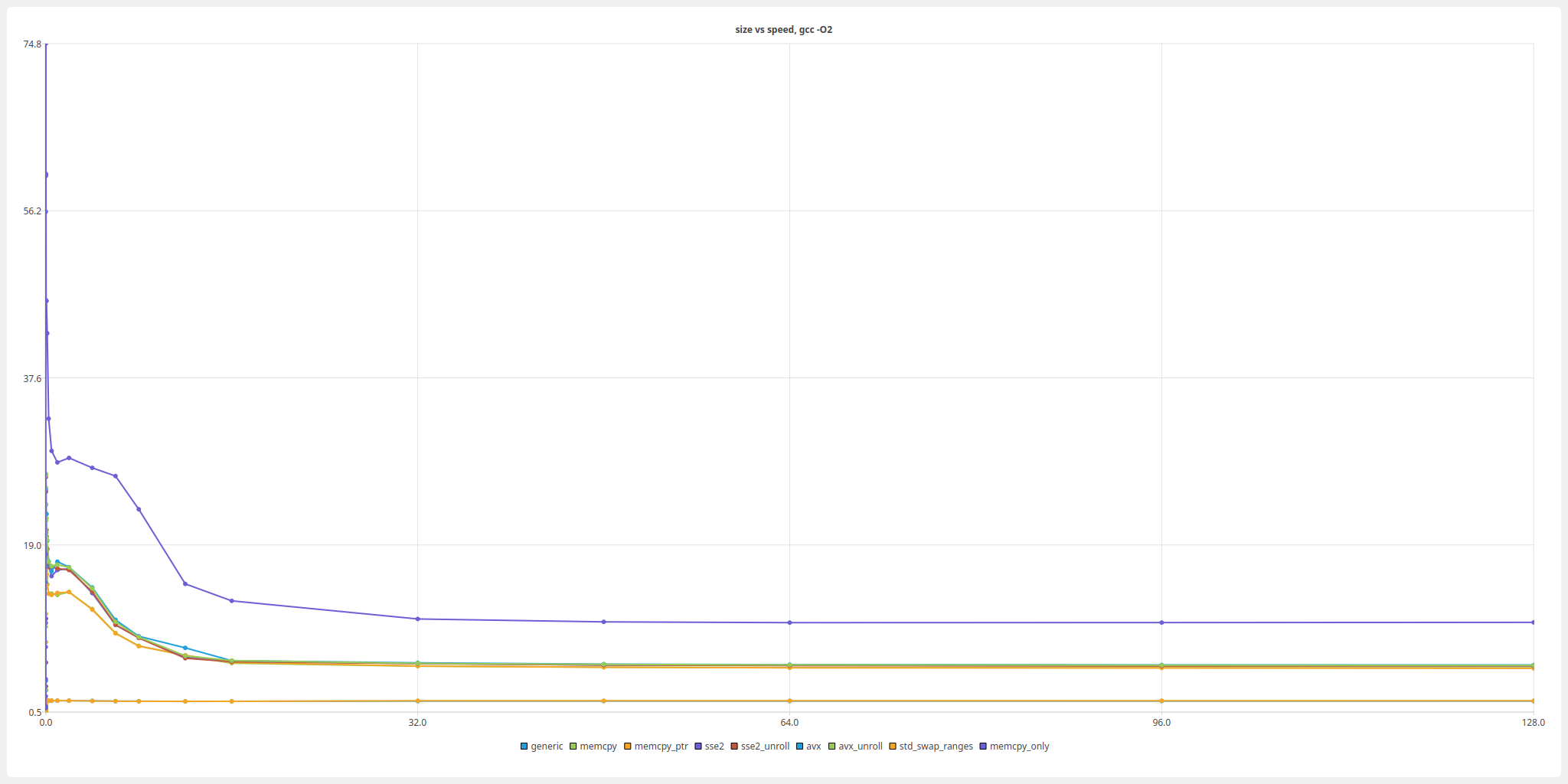

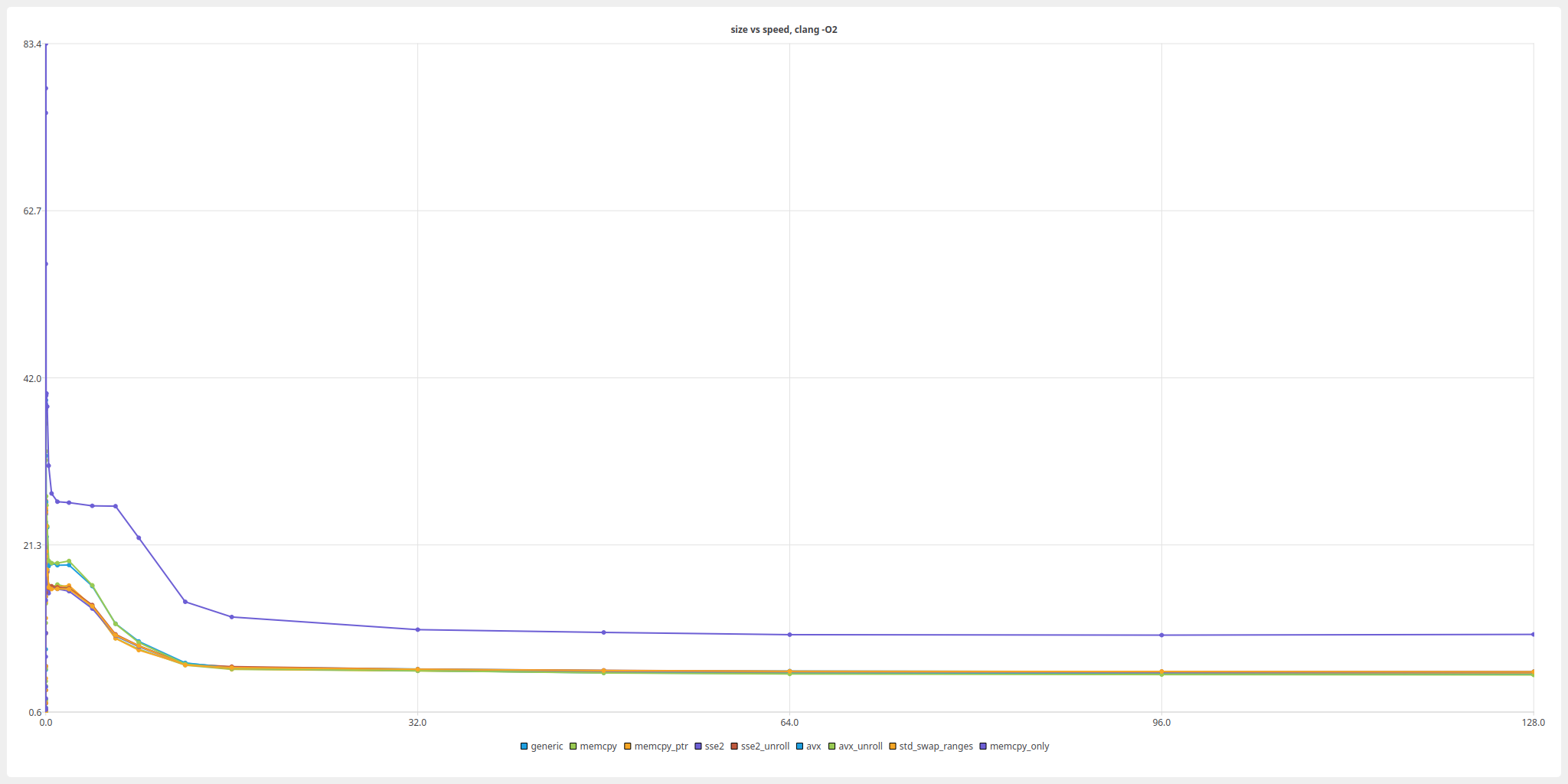

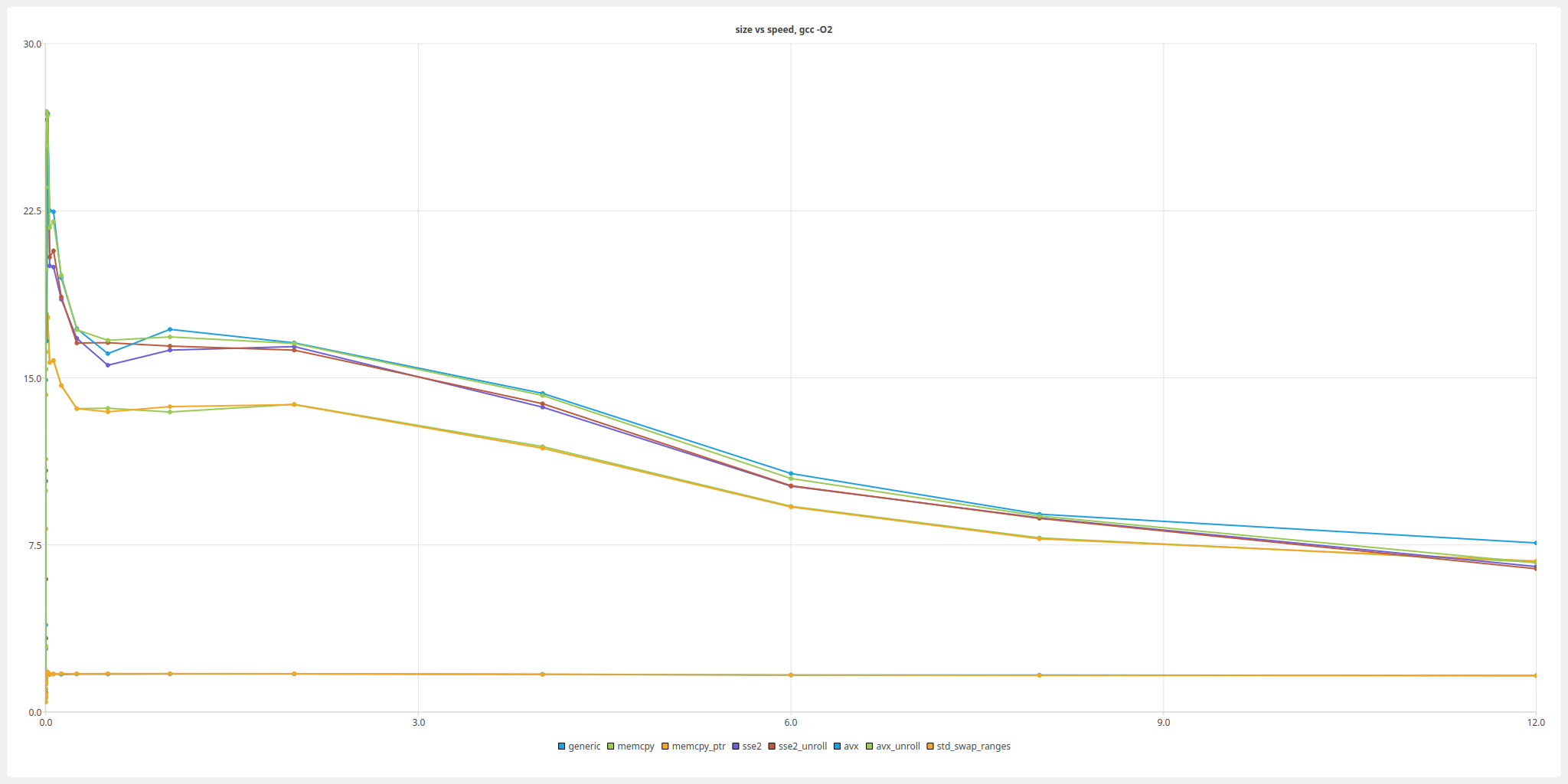

Different buffer-sizes, -O2/ -O3

Lets dig into the optimized builds!

First thing we can see here is that over 12MB all implementations just flattens out at “memory speed” except for the generic implementation and std::swap_ranges() that on GCC performs really bad while on clang the same as the others.

So lets focus on what happens under the L3-cache boundary and remove the pure-memcpy()!

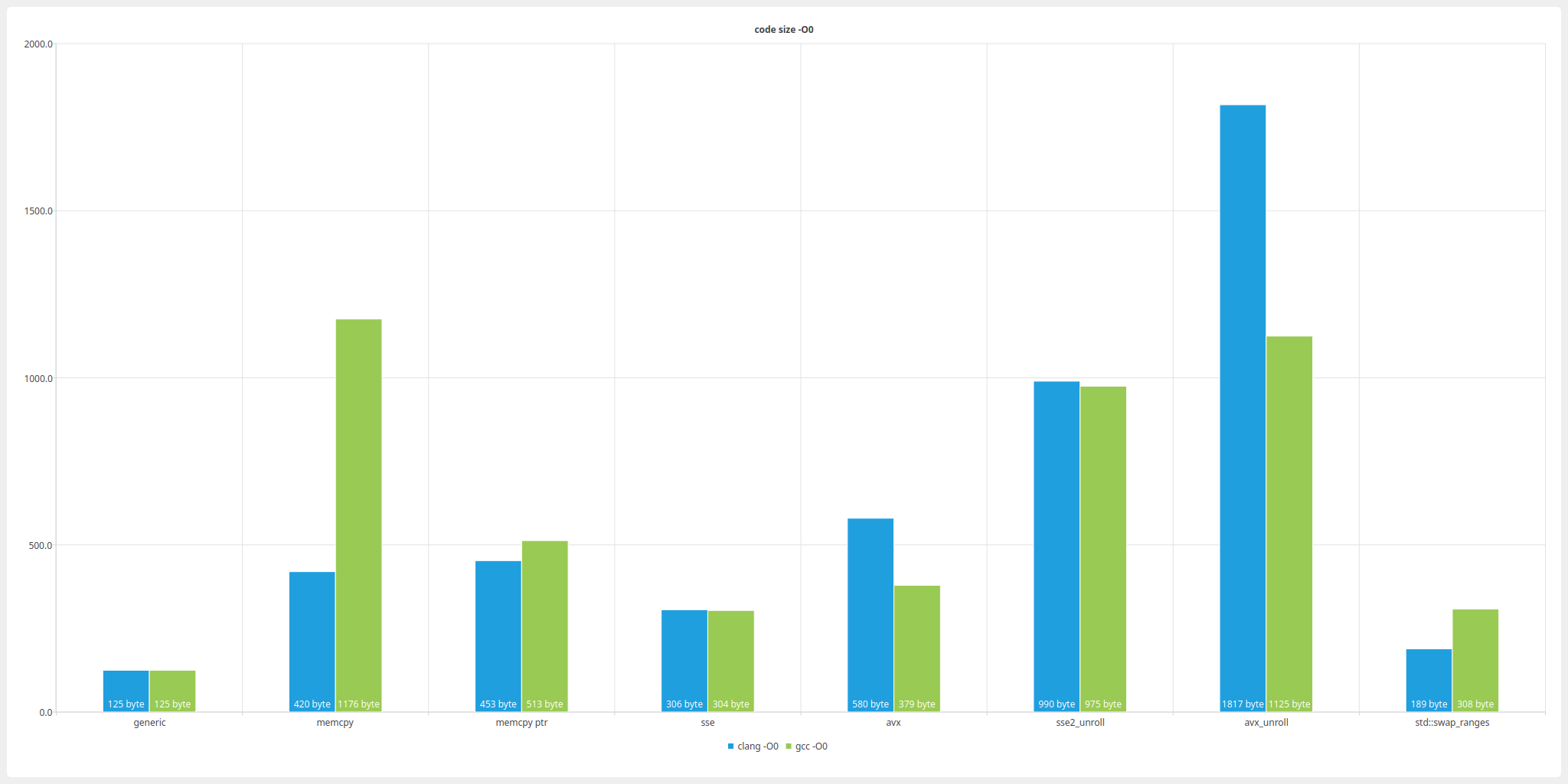

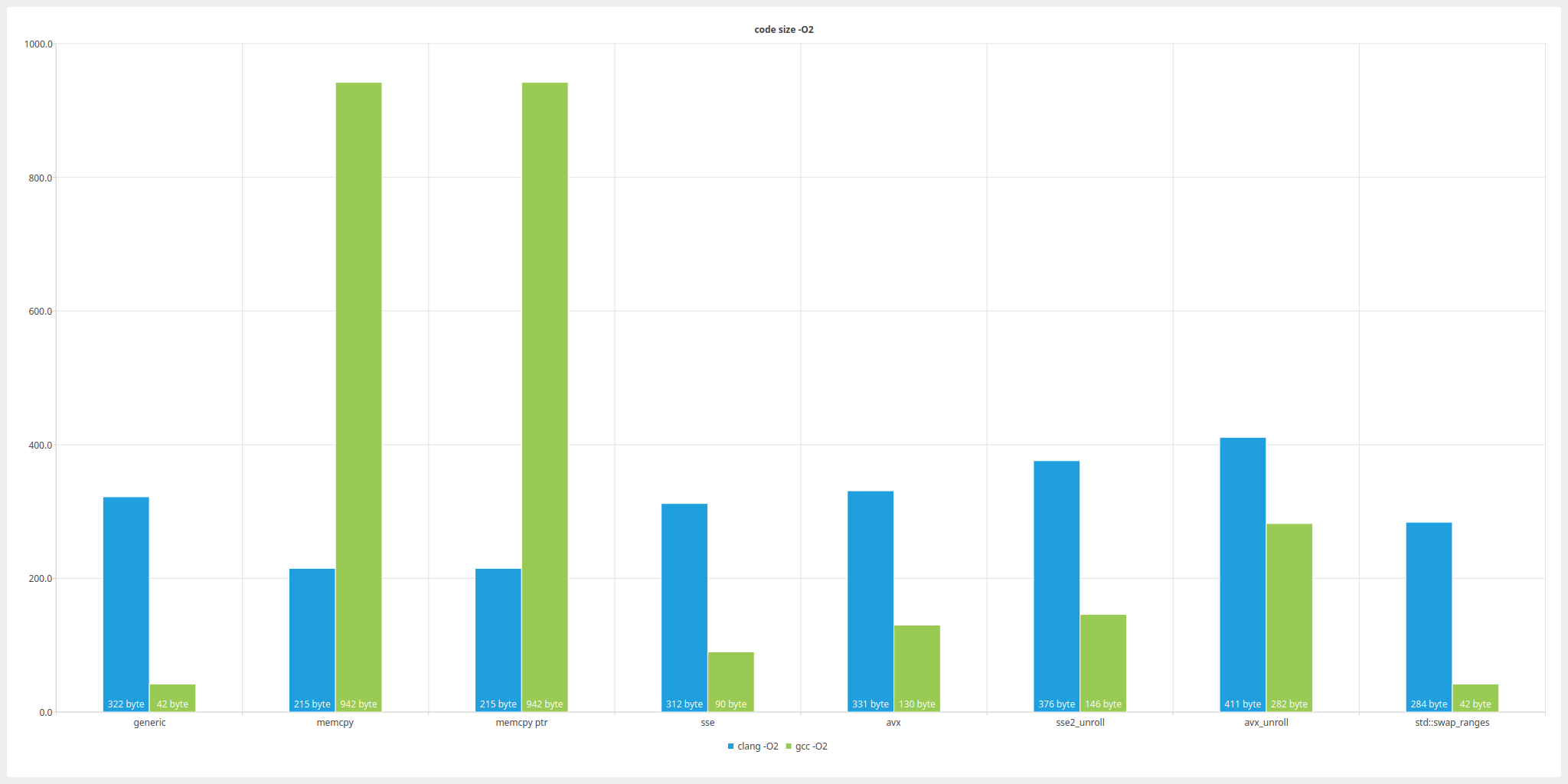

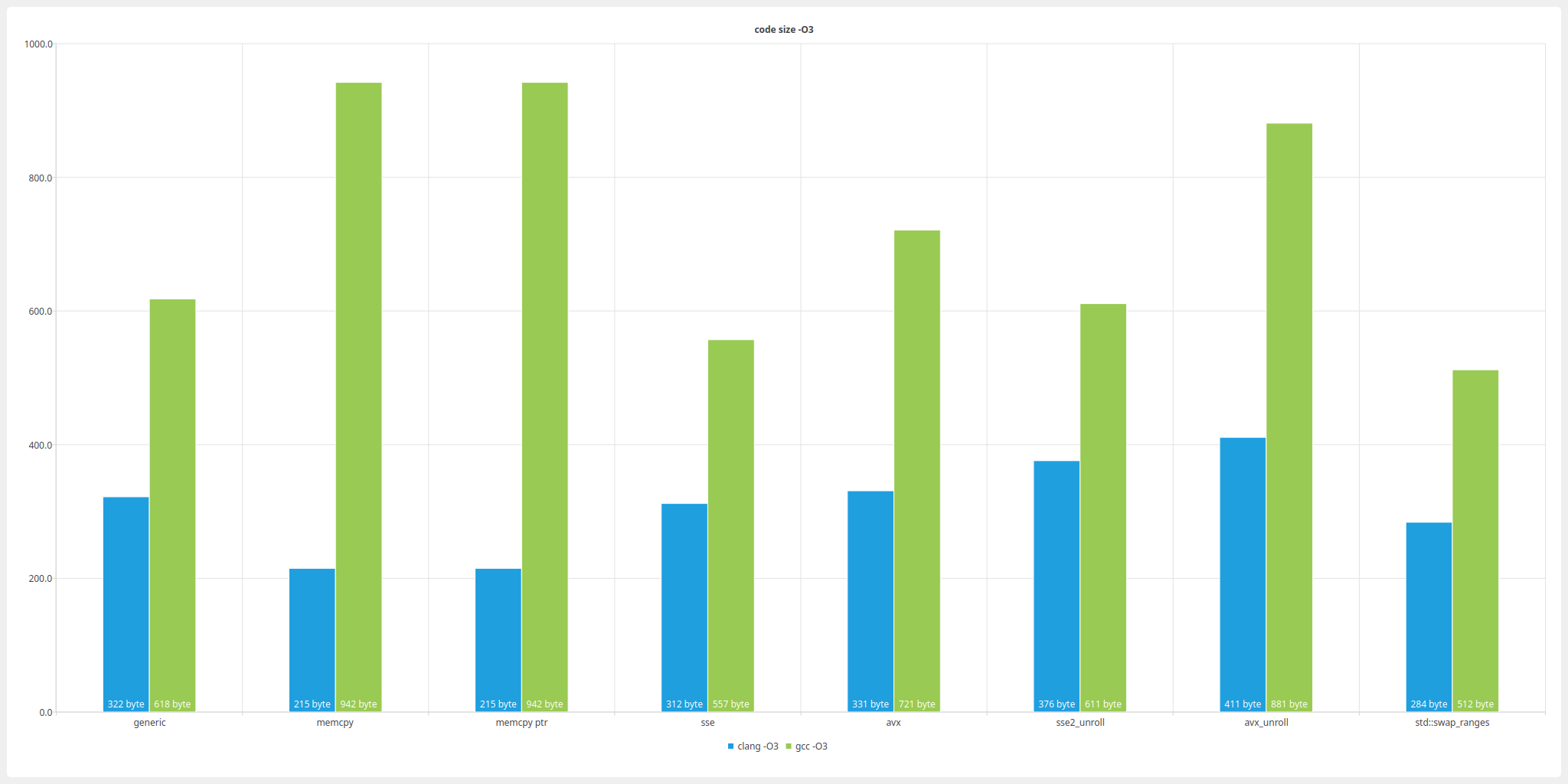

A short note on code size

A short note on code size as we haven’t really dug into it yet. From my point of view code-size of this code is not really interesting. Back in the old days of the PS3 and SPU:s it definitively was, but today I think there is bigger fish to fry. At least for code like this that tend to only be called in a few spots. However if it would be a problem a simple fix would be to just not inline the code as is done now. I doubt that on the kind of buffer-sizes where this would be used that extra call overhead would make any difference what so ever.

However for other sectors of this business I guess it could be of a lot of importance.

So just for completeness, lets have a quick look at code size of the different investigated implementations.

At the time of writing I do not have access to a windows-machine for me to test out msvc on but I will add a few observations on generated code fetched via compiler explorer but no numbers.

dumping function size

For most readers this is nothing new, but dumping symbol/function-sizes is easily done on most unix:es with the use of ’nm’.

nm --print-size -C local/linux_x86_64/clang/O2/memcpy_util_bench | grep memswap

std::swap_rangesin-O0is an estimate and sum of all non-inlined std functions, functions used are

What is most interesting to note is that GCC is, in most cases, generating much smaller code and seem to optimize for that a lot harder. Could that be due to gcc being used more in software where that is more desireable? I can only guess and it surely seems like it.

It would be interesting to hear if there is someone with more knowledge about this than me :)

Summary

So what have we learned? Honestly I’m not really sure :) Writing compilers that generate good code is hard? I feel that both clang and gcc do a decent job at what is presented to them, of course there are more things you can do if you know your problem up front compared to producing an optimized result from “whatever the user throws your way”.

We can also conclude that clang seems to do a better job when it comes to perf compared to GCC, that on the other hand generate smaller code on average. This being true with one caveat, that GCC does a much better job with AVX than clang.

This might seem like ordinary bashing of c++ standard libraries and I really didn’t want it to be… but debug perf is important! Compile time is important! and it seems like it isn’t really taken into account when it should be.

I’m not alone in seeing this. In the last year we have seen other more “c++-leaning” developers also raising this issue. For example Vittorio Romeo has been raising that std::move, std::forward and other “small” function generate expensive calls in debug that really isn’t needed and has been pushing for changes to both clang and gcc + it now seems that msvc is also coming along for the ride with [[msvc::intrinsic]]

See:

and:

Personally I would just like to see less std:: and less meta-programming in the code I work in, but since I work in reality it is kind of hard to avoid so I think work being done on making these kind of things cheaper is very welcome!

It might also be worth noting that I quickly tested out some “auto-vectorization” pragmas and that kind of stuff as well and at a first glance it didn’t change the generated code one bit. I might have done something wrong or just missed something, I don’t think so but I have been proven wrong before :D

Also, during me writing this post gcc was updated in my ubuntu dist and I saw that some of the perf-issues noticed in here had been fixed. We’ll see if it is noticeable enough to warrant me writing more on the topic!

So were do we go from here? There are a lot of things that might be worth looking into in followup posts, things such as:

- What do MSVC do?

- Is it worth looking into some inline assembly in some parts of the code?

- optimizing (and making sure they work as expected) the other functions in memcpy_util.h.

Last words. Was this interesting? Where did I mess up? Want to see more like this? Hit me up on mastodoon and/or “the bird site” and tell me! (As long as you are fairly nice!) If something interesting pops out I might do a followup :)

Apendix

Appendix with asm-listings and tables!